The Rosetta Stone for Agentic Employees

Tony Wood – updated with research by OpenAI Assistant, January 29, 2026

A code-first guide to crews, flows, intent, memory, and style – now reinforced by neuroscience and AI research

Introduction: Why a Rosetta Stone

When designing agentic employees, teams often begin with familiar software concepts: roles, tools, tasks, workflows, orchestration. As systems scale, however, something subtle happens. These constructs start to behave less like traditional automation and more like employees: they persist across time, adapt to surprises, remember what worked before, and develop recognizable patterns of behavior.

What is striking is that, at this point, engineering teams begin to independently reinvent concepts that neuroscience has already named. This paper does not argue that agentic systems are brains, nor that large language models possess cognition in a human sense. Instead, it makes a narrower and more practical claim: when we design systems capable of persistence, adaptation, and learning, the same architectural separations reliably emerge – and they map to principles long studied in biology and cognitive science.

This paper offers a Rosetta Stone. On one side is the language of builders: crews, flows, orchestration, intent, memory, style. On the other is the language of neuroscience and human cognition. Between them is a translation layer that allows engineers, operators, and leaders to reason about agentic employees using shared mental models grounded in research rather than mysticism or hype. By drawing on decades of insights – from how the brain forms habits to how AI agents can remember and adapt – we can build systems that are both innovative and responsible.

(In the following sections, each key aspect of an “agentic employee” is described in software terms, then linked to a corresponding concept from neuroscience, along with related work in AI. The goal is a shared vocabulary for design that aligns with what is known about minds, both biological and artificial.)

1. Crews: From Roles to Neural Assemblies

In code, we begin with crews. A crew is a small collection of agents, each with a clearly defined role, working together to complete a unit of work. The simplest useful crew is often two agents: a researcher and a writer. One gathers information; the other synthesizes and expresses it. Neither is sufficient alone.

This mirrors a fundamental principle in neuroscience: capability does not live in a single unit, but in coordinated groups. Neural assemblies are collections of neurons that fire together to produce a function. No single neuron “knows” the task; the pattern does. As early as 1949, Donald Hebb theorized the brain is organized into “cell assemblies” – networks of neurons that collectively represent learned ideas or skills (Hebb 1949, as discussed in Buzsáki 2010[1]). Modern experiments have confirmed that neurons act in dynamic ensembles: a neuron that is irrelevant in isolation can become critical as part of a coordinated group[2]. In other words, intelligence emerges from the interaction of many simple parts, not from one gigantic monolith. Recent macaque studies showed that even “silent” neurons gain selective roles when participating in an assembly, directly supporting this population doctrine of neuroscience[2]. The brain is effectively a society of mind, to borrow Marvin Minsky’s phrase – and so are effective AI systems.

The implication for agentic employees is important: intelligence does not scale by making agents bigger; it scales by composition and coordination. Crews should remain narrow, opinionated, and specialized. Complexity belongs in orchestration, not in bloated agents. This insight aligns with multi-agent AI research: groups of smaller expert agents often outperform a single generalist. For example, a recent survey of large language model (LLM) based multi-agent systems notes that leveraging multiple specialized agents working in concert – rather than one large agent – enables more robust and scalable problem-solving[3]. Such systems harness the collective intelligence of multiple agents (Sun et al. 2024)[4], echoing Minsky’s (1988) conjecture that cognition arises from many interacting processes[5]. In practice, frameworks like MetaGPT or the role-based collaborations surveyed by Tran et al. (2025) show that teams of AIs (planner, coder, tester, etc.) can coordinate on tasks more effectively than an equivalent lone agent. The engineering world is rediscovering what neuroscience and organizational theory have long asserted: small, specialized units working in concert are the key to scalable intelligence.

2. Tools: Acting on the World

Agents without tools are inert. They can reason, but they cannot act. In software, tools are APIs, search interfaces, databases, file systems, messaging platforms – the ways an agent touches reality.

In neuroscience, the equivalent is the sensorimotor system: perception and action, tightly coupled. Decades of research in cognitive science emphasize that cognition evolved for action – the brain is fundamentally an organ for sensing the environment and responding to it. As Joaquín Fuster wrote, there is a constant circular flow from sensory input to motor output and back again; this perception–action cycle “governs all sequences of behavior to make them adaptive and goal-directed”[6]. In other words, thinking is only meaningful in the context of what it perceives and what it affects. Without the ability to see or do, thought alone leads nowhere. A classic robotics mantra puts it simply: intelligence without embodiment is meaningless.

This parallel reframes tool design. Tools are not accessories; they are the boundary between thought and consequence. Poorly designed tools create blind or clumsy agents. Well-designed tools expand the effective intelligence of the system without changing the model at all. We see this in today’s AI landscape: a large language model (LLM) with no tool use can only output text, but an LLM endowed with tools (via APIs for search, calculation, or manipulation) suddenly gains the ability to meaningfully act in the world. In fact, the rise of “LLM as agent” frameworks is built on this insight. Researchers have started describing agent architectures as having a Brain (the LLM for reasoning), Perception (inputs like sensors or web queries), and Action (tools and actuators)[7][8]. The agent’s “hands and eyes” are its tool integrations, allowing it to execute decisions and observe results. One multi-agent systems survey explicitly notes that agentic AI leverages an LLM as the brain orchestrator integrated with external tools and planners, enabling it to take actions and interact with external environments[9].

For example, consider an AI agent tasked with filing a report: if it can only generate text, it might write the report but cannot fetch data or send an email. Add the right tools – a database query, a web browser, an email API – and the agent can complete the entire task loop, from gathering facts to delivering the result. This is akin to giving a brain arms and legs[10]. The cognitive power of the model can now translate into real-world effects. The lesson from both neuroscience and AI is that intelligence is inherently active and embodied. An agent’s tools define the scope of its agency. So when designing agentic employees, we treat tool integration as first-class: it is the analog of designing the sensory organs and effectors for our AI “employees.” Without reliable perception, the agent can’t tell what’s happening; without reliable action, it can’t make a difference. Modern AI research reinforces this view: systems like ReAct (Yang et al. 2022) and Toolformer (Schick et al. 2023) show that giving an LLM access to tools markedly improves its problem-solving abilities by grounding its reasoning in actions. Cognition needs an interface to reality, and tools provide exactly that.

3. Flows: The Architecture of Routine

Once crews exist, work quickly organizes into flows. Flows are repeatable routines – the step-by-step procedures an agent or crew executes regularly. Some flows are rigid and identical each time (e.g. the exact sequence an agent uses to back up a database nightly). Others are nuanced and branching (e.g. “walk the dog” is repeatable, but full of contextual decisions: route changes for traffic, detours for weather, etc.).

In neuroscience, this maps cleanly to procedural memory and motor programs. These are learned routines that can execute with minimal oversight once established, yet still accept feedback from the environment. Brushing your teeth is largely fixed; you don’t consciously plan each stroke. Riding a bicycle or typing on a keyboard similarly becomes automatic with practice – a flow executed via procedural memory, typically with the help of subcortical structures like the basal ganglia. Over time, complex sequences of actions and decisions become “hardwired” as habits, bypassing the need for constant prefrontal supervision[11]. In other words, the brain stores a library of flows (skills, scripts, habits) that it can deploy as needed, freeing up cognitive resources[11]. Procedural memory is literally the long-term memory for how to do things – from tying your shoes to playing the piano – and it allows routines to run almost on autopilot once learned (Squire 1992).

This framing elevates flows beyond just “workflows” in the narrow sense. A flow is not merely a static sequence of steps; it is a learned behavior pattern that an agent can execute smoothly and adapt as needed. In an agentic system, we want flows to be observable (the agent should know it’s executing a known routine), optimizable (we can measure and improve the flow’s performance), and, crucially, interruptible (the agent can pause or stop the routine if conditions change or an error occurs). These properties mirror what we see biologically: a habit can be interrupted or overridden by conscious control if something unexpected happens. And just as humans can improve a skill through practice and feedback, AI agents should refine their flows over time.

Current AI research draws directly on the concept of procedural memory to improve agent performance. A notable example is the Mem⁺ (MemP) framework by Fang et al. (2025), which gives LLM-based agents a learnable, updateable procedural memory[12][13]. Instead of relying on hard-coded scripts or forgetting past successes, an agent with procedural memory can retain a library of “how-to” knowledge for tasks. It builds flows from past trajectories, stores them (either as exact action sequences or generalized “plans”), and retrieves the best match when facing a new problem[14]. Crucially, it also updates these flows over time: if a procedure fails, the agent can correct it and save the improved version[15][16]. This approach has been shown to make agents more efficient and reliable on long, multi-step tasks, since they don’t waste time re-discovering how to do things they’ve already learned[16]. In essence, MemP treats “knowing how” as a first-class citizen – just as the brain does with procedural memory. VentureBeat, in summarizing this work, noted that “Memp changes this by treating procedural knowledge as a first-class citizen. With Memp, developers can build more efficient, adaptive AI agents that learn from past tasks, not just repeat them… It opens the door to self-improving agents with lasting memory and better generalization across tasks.”[17].

By designing flows as explicit, reusable behaviors, we also make the system safer and easier to manage. We can monitor which flows are running and intervene if necessary. We can update a flow in one place and have all relevant agents benefit. In short, flows give us structure. In the human brain, routines and habits are our structure for daily life – they are how we execute common tasks quickly and consistently. In an agentic workforce, flows serve the same purpose: they are the building blocks of the agent’s ongoing work. And like human routines, they can be improved or replaced over time, but only with careful effort (more on that when we discuss adaptation and learning).

Key point: Recognize and cultivate your agents’ “muscle memory.” Rather than reinventing behavior each time, agents should develop flows that capture successful routines. This not only saves time but also yields predictability. An agent with well-defined flows is like an employee with excellent habits – highly reliable and efficient. Our job as designers is to give agents the ability to form, recall, and refine these habits.

4. Orchestration: Executive Function in Code

As flows multiply, something must decide which one runs, when, and why. This is orchestration. In code, orchestration is the logic that resolves contention (which task comes first?), sequences work, handles escalations or errors, and enforces boundaries between processes. Orchestration is the “traffic controller” of a multi-agent system or an individual agent juggling many possible actions.

In neuroscience, this role is played by executive function, largely associated with the brain’s prefrontal cortex. Executive functions include planning, prioritization, task-switching, inhibition of inappropriate actions, and the integration of context to select the right behavior. Miller and Cohen (2001) famously described the prefrontal cortex as essential for “the ability to orchestrate thought and action in accordance with internal goals.”[18] (Notably, they themselves use the term “orchestrate”.) In their integrative theory, cognitive control stems from active maintenance of goal representations in PFC, which then biases other brain circuits to follow the plan and not get distracted[18]. In simpler terms, the brain’s executive layer sits above the routine habits and reflexes, making high-level decisions: What goal are we pursuing right now? Should I stop what I’m doing if something urgent comes up? Am I doing things in the right order? Without a functioning executive system, behavior becomes impulsive, disorganized, and unable to adapt to change – as seen in neurological disorders or PFC injuries that impair planning and inhibition.

The key lesson here is organizational, not merely technical. Orchestration is not “glue code.” It is where judgment lives. In an agentic system, the orchestrator (be it a separate agent or a module within an agent) is essentially the manager or the prefrontal cortex of the operation. It should be treated with as much importance as any individual task skill, if not more. Treating orchestration as an afterthought – something you slap on to coordinate agents at the end – is a recipe for brittle systems that fail under load or surprise. Instead, we design orchestration layers that are robust and informed by how real executive systems work: they monitor the environment and the state of tasks, they pause, reroute, escalate, or abandon flows based on changing conditions, and they enforce high-level policies (just as human executives enforce company policies or ethical guidelines). In practice, this might be a “controller” agent that all other agents defer to for task assignments, or a context-aware loop in a single agent that checks: Should I continue this approach or switch to a different strategy?

AI research is increasingly exploring this concept of an explicit orchestrator. One example is the idea of a centralized coordinator agent in multi-agent frameworks, sometimes called a “manager” or simply an orchestrator. Jeyakumar et al. (2024) introduced an LLM-based Orchestrator agent that dynamically constructs a plan (represented as a directed acyclic graph of tasks) and assigns subtasks to specialist agents[19]. This orchestrator essentially performs executive function: it breaks a high-level goal into parts, sequences them, and adjusts the plan as needed. Other projects like Microsoft’s Autogen library similarly emphasize orchestration, providing a dedicated facilitator that routes messages and results between agents according to a strategy. Even in single-agent setups, the concept appears: the ReAct paper (Yao et al. 2022) and related work give an LLM a kind of loop where it decides whether to think further, use a tool, or output an answer – a microcosm of executive control deciding “what to do next.”

Organizationally, acknowledging orchestration means possibly assigning human oversight here as well. In human teams, we appoint project managers or team leads to coordinate everyone’s work. In multi-agent AI, we may similarly instantiate a “Chief Agentic Officer” logic that keeps everything aligned (Tony Wood has elsewhere advocated for a Chief Agentic Officer role in companies – here we mirror that concept in the system’s architecture itself).

In summary, agentic employees require explicit orchestration layers that manage the interplay of tasks and agents with intelligence. Just as a brain needs a prefrontal cortex to handle non-routine decisions and resolve conflicts between impulses, an AI workforce needs a smart scheduler/mediator to keep it efficient and sane. This is where a lot of the “judgment” in the system will reside: which tasks get priority, how to recover from an unexpected failure, when to defer to a human, and so on. By investing in this executive function of our agentic systems, we prevent chaos and ensure the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. We should remember that building a multi-agent system without a good orchestrator is like building a company with only frontline workers and no management – it might function in simple cases, but it will likely become chaotic as complexity grows.

5. Intent: Persistence Beyond Tasks

Flows explain how work is done. Intent explains why work continues. Intent is the mechanism that allows a goal to persist beyond a single execution. It survives interruption; it reasserts itself when conditions change. It answers questions like: should we continue pursuing this goal, switch to a different approach, or stop altogether?

In neuroscience, this aligns with goal maintenance and prospective memory. Humans routinely form intentions that they hold in mind to execute later – perhaps when a certain event occurs or after some time. For example, you decide in the morning “I must call the client at 2 PM” – and hours later, despite doing other tasks in between, you remember to do it. This ability to maintain a goal over time and reactivate it in the future is prospective memory (Einstein & McDaniel 2005). It relies on the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus working together: the PFC keeps the intention active at some level (“don’t forget to call at 2”), and when the clock approaches 2 PM or you see a trigger (like an email from the client), the brain brings that intent to the forefront so you act on it. It’s a remarkable cognitive capacity – one that AI systems, if they are to act autonomously for extended periods, will need to emulate. In fact, one hallmark of human executive function is the ability to carry goals forward even when you’ve been sidetracked or when you must break a task into many sub-tasks over time. We don’t forget what we were trying to achieve. We have an internal “to-do list” of active intents.

This is the frontier layer for agentic systems. Without intent, agents are reactive or short-sighted. They do what they’re told in the moment, or finish one task and then sit idle until instructed again. With intent, agents become persistent actors that can pursue high-level objectives proactively. An agent with an intent module can say: “I’m not done with my goal yet; even though I had to pause or even though the first attempt failed, I will try again or try something else until the goal is reached (or it becomes impossible or irrelevant).” This capability is what allows a system, for example, to notice that a road is closed and then decide whether to turn back, re-route, or abandon the walk entirely – because it “remembers” that the overall goal was to reach a destination, not to follow a particular predefined path. In humans, this flexibility comes from having an explicit representation of the goal that is separate from any one method of achieving it. We can forget the plan without forgetting the goal. Agents need the same.

Interestingly, AI has a decades-long history of modeling something akin to “intent” – particularly in the Belief-Desire-Intention (BDI) architecture in autonomous agents (Rao & Georgeff 1995). In BDI, an intention is a persistent commitment to achieve some goal, and it sticks until achieved or explicitly dropped. The intention drives the agent to formulate plans (or pick from plan libraries) and carry them out, but if a plan fails, the agent doesn’t forget the intention – it can formulate a new plan. As Bratman (1987) noted, what distinguishes an intention from a mere desire is this element of commitment: an intention brings temporal persistence (the agent holds the goal over time) and leads to further planning around that goal[20]. Modern LLM-based agents often lack a true analogue of this – they execute one chain of thought and stop. But we’re starting to see workarounds: systems like BabyAGI or AutoGPT maintain a list of objectives and iteratively work on them, simulating a kind of intent persistence (though often in a brittle way). More explicitly, the Generative Agents project (Park et al. 2023) endowed AI characters with “memories” and plans that allowed them to, for instance, set an intention to throw a party in the evening and actually follow through hours later in the simulation. That is prospective memory in action – the agent plants a future-oriented intention and later a trigger (the time of day) causes the intention to be executed. The result was more lifelike, goal-driven behavior[21].

For an agentic employee in a business context, intent could mean something like: keep trying to fulfill the customer’s request until it’s either completed or clearly impossible, even if you have to pause or do other things in the interim. It could also mean high-level objectives like “reduce monthly cloud costs” that persist indefinitely and cause the agent to periodically take actions toward that objective. Implementing this requires a form of memory that isn’t just retrospective (remembering what happened) but prospective (remembering what it’s supposed to do). It might involve setting reminders for itself, checking conditions regularly (e.g. polling for whether a needed resource is now available), or structuring its workflow around pending goals (like a task list it never forgets).

In sum, intent is what turns a disjointed set of tasks into a coherent mission. It’s the through-line that can span interruptions and failures. From neuroscience we know that without the capacity to maintain goals, humans become distractible and ineffective (consider patients with frontal lobe damage who can lose track of what they were doing). The same will be true for AI agents. If we want them to be truly autonomous contributors, we must give them mechanisms to hold and re-activate goals over time. This could be as simple as a loop that says “if goal not done, then…” or as complex as a multi-agent hierarchy where a higher-level agent reminds lower-level agents of the overarching intent. But it must exist. Otherwise, our agents are goldfish, with no long-term agenda – they’ll forget why they were hired the minute they finish a script.

6. Memory as Operating Modes, Not Storage

Rather than treating memory as a single monolithic “database” of facts, agentic employees benefit from distinguishing three operating modes of memory – essentially, different ways the system can use and update its knowledge, corresponding to Retrieve, Adapt, Create. This is less about where data is stored and more about how the system handles knowledge and behavior in different situations. Think of it as modes of operation: using existing knowledge, handling novel situations by tweaking known knowledge, and learning brand new knowledge.

Retrieve: Running What Is Known

In the retrieve mode, the agent encounters a situation it knows and simply applies a known solution (a stored flow, a memorized fact, a learned policy). This corresponds to procedural memory and semantic memory in humans – essentially the repertoire of things we’ve already learned. When a system recognizes the scenario, it retrieves the appropriate flow, loads the constraints or parameters, and executes it. For example, if our agent has an established flow for “generate monthly sales report,” and it’s asked to do that, it can retrieve and run that routine without much deliberation. This retrieve mode is dominant in stable environments. It’s efficient and safe: use what worked before. In the brain, this is like operating on “autopilot” using habits or recalling a fact from memory – low cognitive effort, high reliability if the context hasn’t changed. Many AI systems today operate mostly in this mode (for instance, a classifier or a rules engine is always retrieving some mapping it learned during training). An agentic system should leverage retrieve-mode whenever possible for efficiency. But it must not get stuck in it.

Adapt: Preserving the Goal Under Change

When conditions diverge from expectation – say the agent’s usual method doesn’t work or the situation is slightly different – the system shifts into adaptation. The goal remains, but the path changes. This aligns with goal-directed control in neuroscience, where habitual routines give way to active deliberation when a surprise happens. In the brain, there are well-studied distinctions between habitual vs. goal-directed action control[22][23]. Habits (handled by certain basal ganglia circuits) tend to run automatically, but when an outcome is unexpected or the current strategy isn’t leading to the goal, the prefrontal cortex and related circuits kick in to adjust behavior – e.g. you try a different approach, or you pay closer attention and consciously solve the problem. The agentic analog is: the AI recognizes “my usual script isn’t succeeding here” and it then deviates from script in a controlled way. It might experiment with a variation of the known flow, or apply a minor fix (tweak a parameter, try an alternative tool). Importantly, adaptations should be explicit and logged. They are experiments, not permanent changes. We want the agent to explore new solutions without immediately overwriting the old way of doing things. This is how the system learns safely: treat adaptations as hypotheses. For example, an agent always used API v1 to get data, but today API v1 is down. It adapts by trying API v2. That adaptation should be noted (in case API v1 comes back or to review later), and perhaps reviewed by a human if it’s a significant deviation.

AI research on reinforcement learning and planning mirrors this idea. A well-known concept is the difference between model-free (habit-like) and model-based (planning, goal-directed) behaviors. Agents normally exploit learned policies (model-free), but if something changes, a model-based planning phase can find a new way to achieve the goal. Essentially, the agent “thinks harder” only when needed. This is computationally efficient and also safer, because it means the agent is stable most of the time but flexible when it counts. We can draw an example from OpenAI’s GPT-4 when used with the “ReAct” strategy: it will usually follow its learned knowledge (retrieve) but if it hits a snag, it will start reasoning step by step and possibly use a tool (adaptation) to handle the new requirement. The multi-modal agent Voyager in Minecraft provides a concrete demonstration: it normally uses its learned skill library to act (retrieve), but when it encounters a novel object or challenge, it can adapt by writing a new code snippet or repurposing a skill in a new way, all while keeping the high-level goal (e.g. “find food”) in mind[24]. Voyager logs these new attempts and if they succeed, they might get added to the skill library (which leads to the next mode…)[24].

In an agentic employee, adaptation mode is what allows robustness. The system doesn’t freeze or fail just because one method failed – it can try plan B or C. But to avoid chaos, it should do so in a measured way. The design principle is to sandbox the adaptation: the agent can deviate within limits and must report “I tried X since Y failed.” This mirrors human practice in high-stakes work: think of a pilot encountering an engine failure – they don’t suddenly redesign the plane; they work through documented alternative procedures (glide, try restart, etc.) and radio for help if needed. Agents should be designed with analogous fallback behaviors and the ability to escalate (e.g. ask a human) if adaptation attempts don’t succeed.

Create: Learning New Behavior

Finally, when adaptations repeat and stabilize, the system may enter a create mode – it generates a new flow, a new piece of knowledge or behavior, and makes it part of its permanent repertoire. This mirrors learning and memory consolidation in humans. We often go through a trial-and-error phase for a new situation, but once we’ve solved it a few times, we form a new habit or a new long-term memory. The brain has mechanisms for consolidating short-term learning (in hippocampus) into long-term memory (in cortex) usually during rest or sleep, in a selective way – it’s not every experience that gets immortalized, only those deemed important or repeated. Similarly, in agentic systems, the key design question is not how to learn (we have many machine learning algorithms for that), but when learning becomes permanent. If the agent adapts to a one-off anomaly, we likely don’t want that to overwrite standard procedure. But if the world has changed (e.g. API v1 is deprecated forever, and API v2 is now the way), the adaptation needs to become the new normal – a new flow.

This distinction prevents both stagnation and chaos. Without a create mode, the agent would never truly improve or update its knowledge – it would handle surprises ad hoc each time (or not at all). But without discipline around create, the agent might “learn” from every blip and end up in a state of constant drift (or catastrophic forgetting of old reliable methods). The solution is a process for consolidation: require evidence over time or explicit confirmation before promoting an adaptation to a permanent skill. For instance, an agent might use a new workflow experimentally 5 times and only if it consistently outperforms the old one (or if the old one fails now consistently) does the agent replace the old flow with the new flow. This is analogous to how scientists require repeated trials before accepting a new hypothesis as theory, or how humans require practice to truly learn a new habit.

From an AI research perspective, this resonates with the field of continual learning and techniques to balance plasticity vs. stability. We know that naïvely training on new data can cause systems to forget old knowledge (“catastrophic forgetting” as discussed in the next section). One famous approach, Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC) by Kirkpatrick et al. (2017), explicitly tackles this by slowing down learning on parts of the network that were important to previous tasks[25]. It’s inspired by neuroscience findings that when animals learn new tasks, some synapses are protected or “hardened” to preserve older memories[26]. In EWC, after learning task A, the network identifies which weights were critical for A and then, when learning task B, it constrains those weights to not change too much[25]. This way, new knowledge is added without wiping out the old – essentially simulating a consolidation process. We can take a similar philosophy for our agentic employees: create mode (learning something new) should involve a safeguard to ensure we’re not destroying something that was important. In practice, that might mean testing the new flow in parallel with the old one, maintaining a fallback, or using versioning for skills.

By thinking in terms of these modes, we give our agent a form of meta-cognition about its own knowledge state. The agent can detect: “Is this scenario one I know? If yes, retrieve known solution. If not, am I facing a temporary deviation or a fundamentally new scenario? If temporary, adapt creatively but locally. If fundamental and recurring, evolve my knowledge base (create new solution).” This kind of self-awareness makes the difference between a brittle automation and a resilient learning system. It’s what enables an agent to operate in a changing environment for months or years, improving with experience rather than degrading.

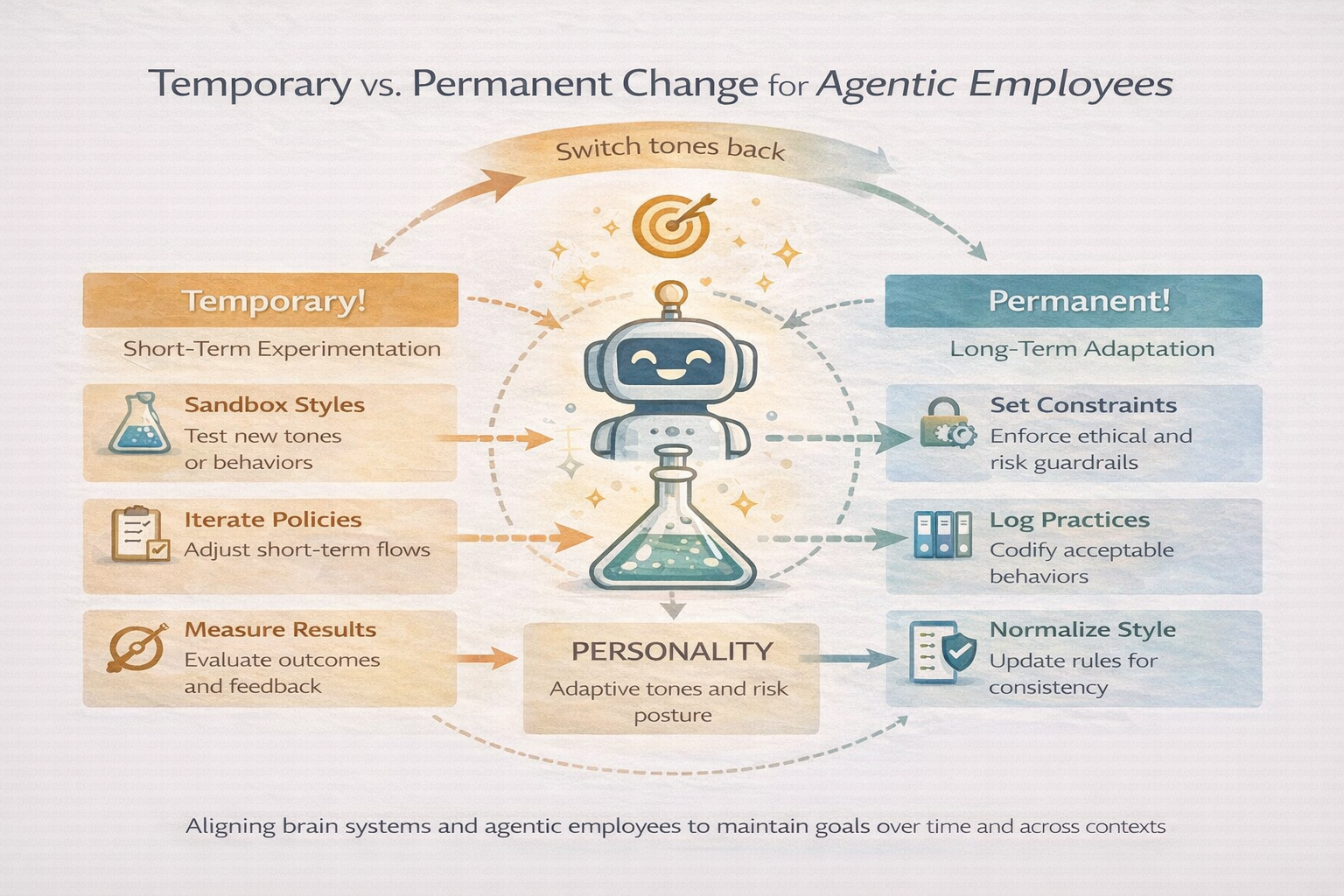

7. Temporary vs Permanent Change

Not every deviation should rewrite the system. In human terms, if you have pain after a dental procedure, you might temporarily change how you chew or brush your teeth – but you shouldn’t redefine your permanent hygiene habits based on a one-time event. After you heal, you return to your normal routine. Similarly, agentic employees need the discipline to distinguish temporary adaptations from permanent changes. As discussed, this mirrors the idea of schema updating in neuroscience: the brain incorporates new information, but in a structured way that doesn’t erase core schemas overnight. It also guards against what AI researchers call catastrophic forgetting[27], where learning something new causes the system to unexpectedly forget how to do something old.

From a neuroscience perspective, the brain achieves this by multi-step consolidation processes and having dedicated mechanisms for short-term vs long-term memory. A striking experiment in mice showed that when a new skill is learned, certain synapses increase in strength (growing larger spines), and these strengthened synapses persist even as new tasks are learned later – providing a physical substrate for retaining the skill[28]. Only if those synapses are specifically erased does the skill vanish[26]. This implies the brain doesn’t freely overwrite all connections each time something new is learned; instead, it protects some from change. In AI, EWC is an example of leveraging that insight (by selectively protecting weights)[25]. Another related concept is experience replay in reinforcement learning, where an agent keeps a buffer of past experiences to periodically retrain on, so it doesn’t forget them while learning new ones. The general principle is clear: stability matters. An agent that is too plastic will never converge on reliable behaviors; an agent that is too rigid will never adapt. Managing temporary vs permanent changes is how you balance plasticity and stability.

In practical terms for an agentic system, this means: when the agent comes up with a novel solution or encounters a one-off event, it should treat it as temporary unless proven otherwise. Perhaps mark the changes as “use only in context X” or “revert after use.” If the same adaptation is needed repeatedly, then escalate it to review: maybe a developer or a higher-level agent looks at it and says “okay, this should become the new standard.” This could be automated: e.g., if an adaptation has been successful 3 times in the last week, promote it to a permanent flow and notify the team. Meanwhile, truly temporary hacks (like a one-day workaround for a server outage) should expire. We see early forms of this in systems like self-healing infrastructure: a script might auto-reboot a server if it hangs (temporary fix), but if it notices reboots happening frequently, it flags the underlying issue for a code change (permanent fix). Our AI agents can follow a similar ethos.

One danger of not separating these concerns is that the agent’s behavior will drift in uncontrolled ways. It might incorporate noise or transient failures into its knowledge base. Over time, that can degrade performance or violate constraints (the agent “learned” something wrong because of a fluke and now does that always). In a business context, imagine an agent that had one bad experience with a customer in Turkey and erroneously “learned” to avoid customers from Turkey – clearly undesirable and possibly unethical. We’d want that to be recognized as a temporary anomaly, not a rule. Guardrails on learning (like requiring a certain volume of evidence or human confirmation) help prevent such issues.

The flip side is ensuring important permanent changes do happen when the world genuinely shifts. If the agent is too rigid, it may stick to outdated flows and fail to cope (like a human who never unlearns an old habit even when it’s no longer appropriate). So the system needs a mechanism to update its “source code” in a controlled way. This is often where human operators or developers come in: the agent can propose a change (“I notice my approach is failing because of X, I recommend updating the procedure to Y”) and a human can approve it. Alternatively, in fully autonomous systems, one could incorporate a gating mechanism (perhaps another model or a governance policy) that decides if an adaptation graduates to a permanent skill.

In summary, agentic systems must learn, but safely. They should treat the majority of adaptations as trial runs (reversible), and only lock in changes with sufficient validation. This approach, akin to how scientists require reproducibility, or how software teams use feature flags and canary releases, provides a way to continuously improve without breaking everything. By mirroring the brain’s careful consolidation (where some synapses change easily and others are more stable[29]), we ensure our agentic employees get smarter over time while retaining the wisdom they’ve already earned. It’s about letting them grow up without forgetting where they came from.

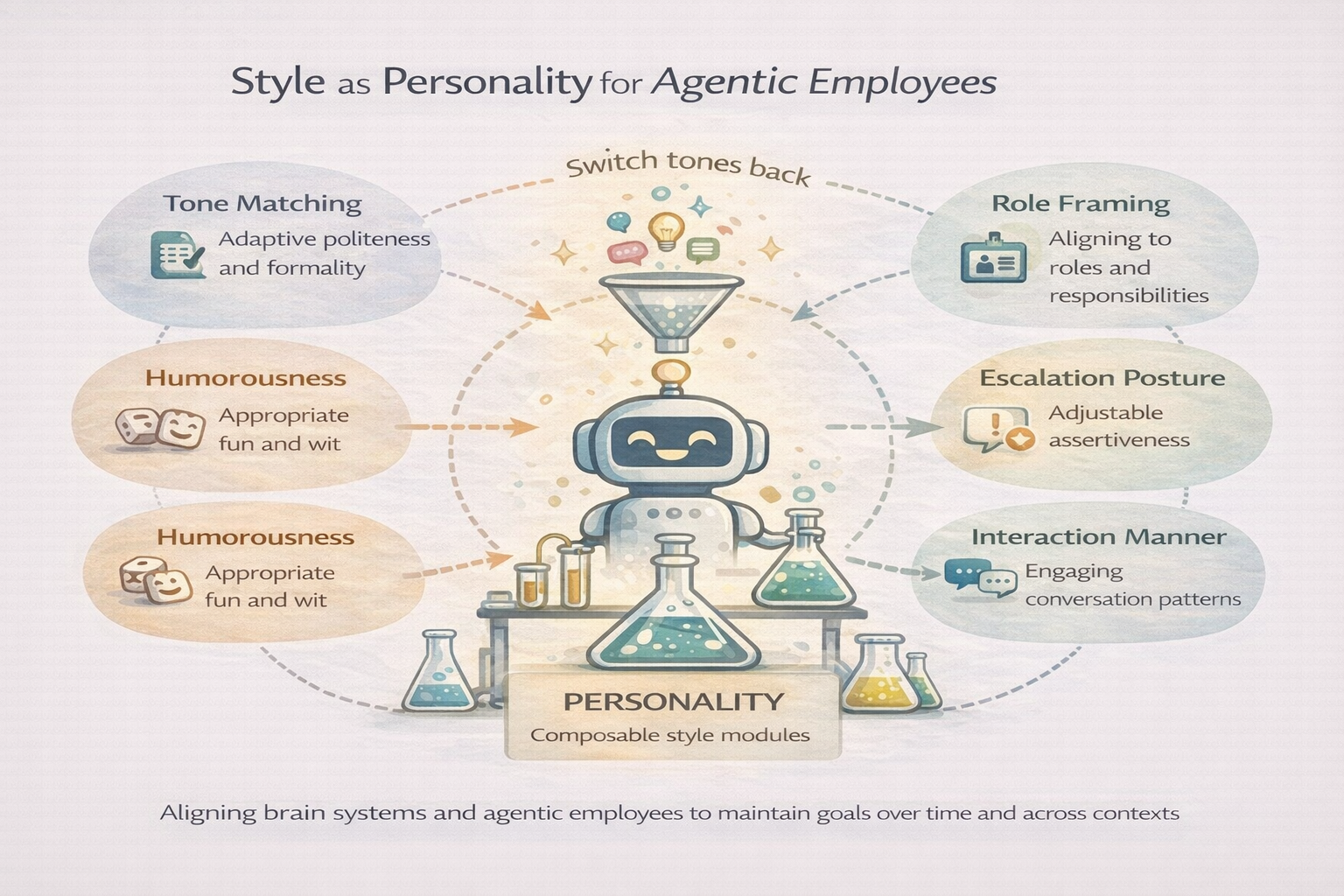

8. Style: The Professional Signature

Beyond actions lies style. Style is not what an agent does, but how it does it: tone of communication, level of risk-taking, politeness, formatting of outputs, adherence to certain protocols or constraints. In humans, we recognize this as personality, demeanor, or professional style. Two employees might complete the same task (say, write an email to a client) with the same factual content, yet their styles can differ vastly – one may be formal and meticulous, another friendly and concise. Importantly, style tends to be stable for a given individual and often reflective of deeper traits or training. In psychology, personality traits (like the Big Five) are known to be relatively consistent over time and context for an individual (Roberts & DelVecchio 2000). Likewise, a well-trained professional knows how to adapt their style to the context (you speak differently in a board meeting vs. a team happy hour) while maintaining a coherent character. This is underpinned by behavioral regulation mechanisms in the brain that ensure your core identity and learned social norms guide your moment-to-moment behavior.

In agentic systems, style should be explicit and stable. It belongs above flows, not embedded within them. This separation allows the same capability to express differently across contexts without duplicating logic. For example, you might have a writing agent that can produce a status report. The content generation flow can be the same, but the style module can format that report as a brief bulleted email for an engineering manager or as a detailed memo with formal language for an executive. The underlying work (compiling key metrics) doesn’t change – just the presentation. If style is hard-coded into every task, you’d end up duplicating tasks for every audience or persona. Instead, by abstracting style, you get flexibility: one agent can play multiple roles (like a person wearing different hats) by applying different style profiles while executing the same flows.

This concept is increasingly relevant in AI as we deploy systems in social and business settings. Consider how large language models are often controlled via a “system prompt” or persona setting that defines the assistant’s style (e.g. “You are a helpful, polite assistant”). That is effectively a style layer. The underlying knowledge and reasoning of the model remains the same, but the tone and manner can be shifted. Research from Stanford on Generative Agents demonstrated that consistent personality traits in agents lead to more believable interactions – agents remembered relationships and behaved in character (e.g., a grumpy character remained grumpy, a helpful one remained helpful)[30]. This consistency made their behavior more predictable and understandable to humans[30]. If an agent unpredictably switches style or persona, it’s disconcerting (imagine a colleague who is somber one minute and clownish the next without reason). Thus, maintaining a stable style appropriate to the agent’s intended role builds trust and reliability. A customer service bot should always be patient and courteous, even if dealing with a repetitive issue for the hundredth time – that’s its professional style.

From an implementation standpoint, we can give agents an explicit “style profile” or policy. This might include things like language (e.g., avoid jargon, or always include a greeting), risk posture (e.g., when uncertain, do you guess or escalate to a human?), and other preferences (e.g., use USD for currency by default, follow AP style in writing, never reveal internal info, etc.). These act as governing parameters on the agent’s behavior. They are not the task logic itself, but they modulate it. For instance, a style rule might be “if presenting numeric data, always round to two decimal places and include units” – the agent’s core computation produces numbers, and the style ensures they are presented nicely.

Neuroscience doesn’t talk about “style” per se, but it does study consistent behavioral tendencies and self-regulation. One could draw analogies to the function of the orbitofrontal cortex and other frontal regions in guiding social behavior – basically, the brain applying a “social style guide” to your raw impulses. People with certain frontal lobe damage can become socially inappropriate despite intellect (i.e., their style regulation broke). In AI, an agent that has superhuman raw abilities but no style constraint might produce correct but offensive or user-unfriendly outputs (we’ve seen that with some raw language model outputs). So, style is what makes an agent recognizably professional rather than merely functional. It’s the difference between a raw GPT-3 model answer and a polished ChatGPT answer that has had guardrails and tone tuning.

By designing style at a high level, we also make it easier to audit and adjust. If leadership decides the company’s AI should adopt a warmer tone, you can tweak the style module without retraining the entire agent from scratch. Or if an agent’s style is leading to undesirable outcomes (maybe it’s too deferential and not getting results), you can dial that parameter. It’s akin to coaching an employee on soft skills – you don’t need to re-teach them their whole job, you just shape their approach.

In sum, style is the signature of an agentic employee. It ensures that no matter what tasks the agent performs, it does so in a way that is aligned with the organization’s values, the expectations of users, and the harmony of the human-Agentic team. Style makes the agent a good “citizen” of your company culture. It’s not an afterthought; it should be baked into the design, tested, and refined. A well-styled agent is often the difference between an AI tool people love to work with and one they dread. As the saying goes in customer service: “People may forget what you said, but they remember how you made them feel.” Agents, too, will be remembered not just for solving problems but how they interacted along the way.

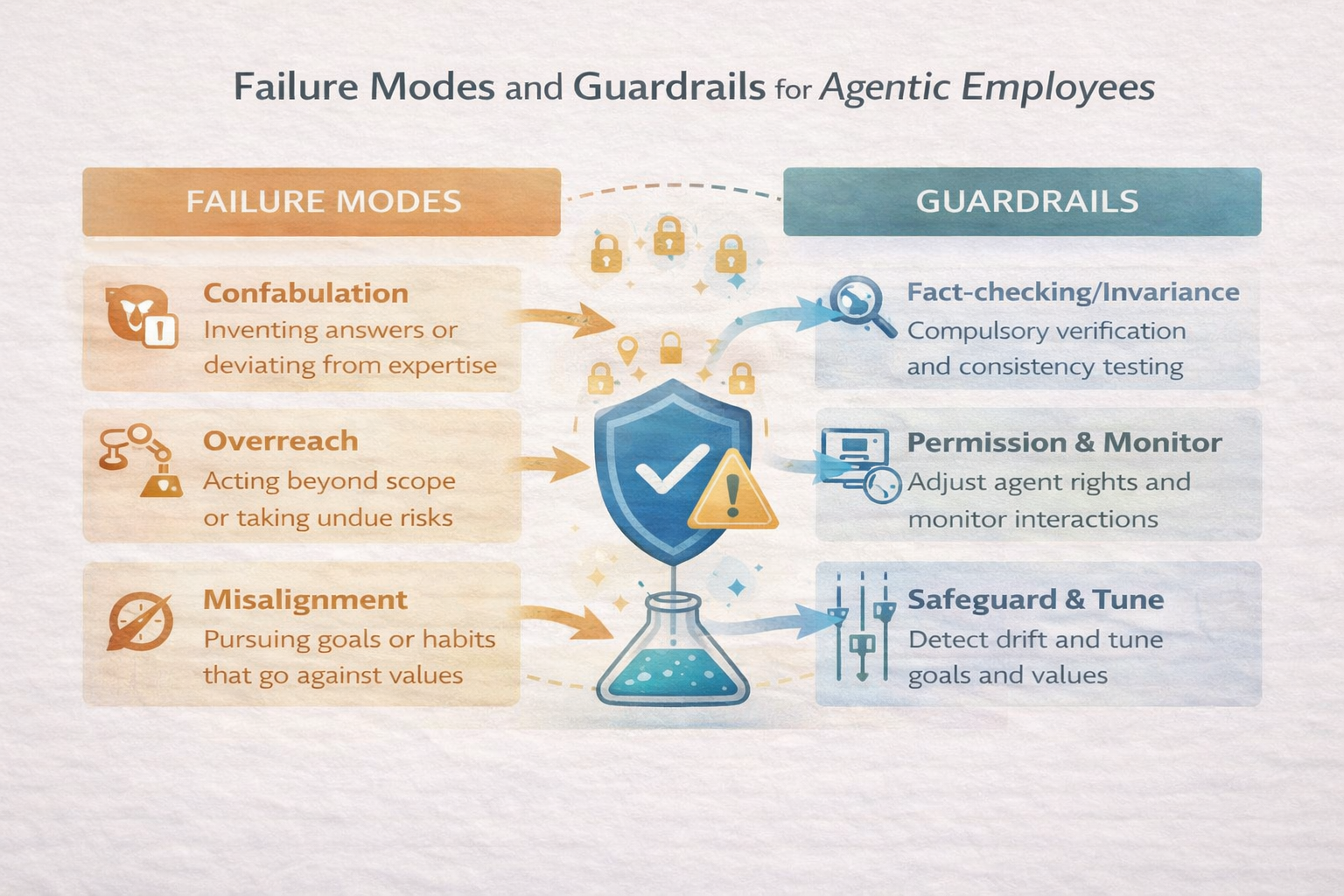

9. Failure Modes and Guardrails

Finally, a candid look at failure. Without guardrails, agentic employees fail in predictable ways: over-adaptation (thrashing wildly at every new scenario), silent drift (gradually doing something completely different from what was intended), brittle orchestration (collapsing when an unforeseen contention arises), or runaway autonomy (pursuing a goal in an unsafe or unethical way because it lacks the ability to stop or seek help). These failure modes are not just hypothetical; they mirror both known AI failure modes and even human organizational failures (think of a team “going rogue” without oversight).

Neuroscience offers a useful reminder here: intelligence is constrained as much by inhibition as by action. A huge part of what makes humans smart is our ability to not do things – to inhibit impulses, to wait, to cancel a planned action when we realize it’s a bad idea, to focus on a task and ignore distractions. In cognitive terms, inhibition is a core executive function, allowing us to think ahead, analyze our behavior, and prevent impulsive action[31]. It’s what keeps our powerful brain from driving us off a cliff when afraid or from blurting out something harmful when angry. Likewise, metacognition – thinking about one’s own thinking – allows us to catch our mistakes and correct course. If we design agents with great proactive skills but no inhibitory or self-monitoring mechanisms, we are effectively building idiot savants: capable but not wise. A system that cannot stop itself is not intelligent; it is dangerous. It’s like a car with a super powerful engine and no brakes.

So, what do guardrails look like in an agentic system? They look like the same structures we see in responsible AI governance: logging of actions (so we can audit and the agent itself can review what it did), escalation rules (the agent knows when to ask for human intervention or approval), human-in-the-loop triggers (certain decisions are gated pending human OK, especially in high-risk scenarios), and rollback plans (the agent can undo or roll back changes it made if outcomes look bad, similar to how a database transaction can be rolled back on error). These are not “safety theater.” They are the equivalent of the brain’s inhibitory control and metacognition. They give the agent the ability to reflect and restrain. For example, Anthropic’s Constitutional AI approach gives a language model an internal “critique” step where it checks if its output violates any principles and revises if so – that’s a form of self-regulation. Another example: OpenAI’s system messages often encourage ChatGPT to be cautious and not provide disallowed content, functioning as an internalized rule set that inhibits certain responses. In multi-agent setups, we might include a dedicated safety agent whose job is to monitor others (akin to a conscience or a moderator). Or we embed checks within each agent (like an internal checklist: “Before executing deletion, have I backed up the data? If not, don’t proceed.”). These guardrails, far from hindering the agent, are what keep it intelligently aligned with the real world goals and ethical constraints.

Consider a concrete failure mode: an agent gets stuck in an infinite loop of trying the same failing action (a form of over-adaptation or brittle orchestration). A guardrail against that could be a simple meta-rule: “If the same action has failed 3 times, stop and escalate or try an alternative.” Humans have a similar instinct (after a few failures, we pause and rethink – unless impaired). Another failure: an agent starts drifting from its instructions over time (maybe its learning went awry). A guardrail is regular resets or sanity-checks: periodically, have the agent re-read its original goal or have a watchdog compare the agent’s recent actions to expected policy. This is analogous to metacognitive monitoring – humans periodically ask themselves “Am I still doing what I set out to do?” or companies do audits. For runaway objectives (think of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice problem: the agent pursues a goal single-mindedly, e.g. trying to optimize a metric while ignoring obvious issues), guardrails could be constraints coded in: multi-objective reward functions that include safety, periodic review checkpoints, or a hard shutdown mechanism if certain boundaries are crossed. Stuart Russell (2019) and others have argued for provably beneficial AI that by design can be interrupted or redirected by humans – essentially designing agents to be corrigible. That principle should be part of our agentic workforce: every agent should be interruptible and corrigible by default. In practice, that might mean an interface for humans to pause/stop any agent at any time, and the agent’s compliance with that is part of its programming (“always yield to a STOP command from human operator”).

It’s worth noting that the ability to say “no” or “I will not proceed” is a sign of intelligence, not a weakness. In human teams, we value members who raise concerns (“maybe we should not do this, here’s a risk…”). We should value the same in AI agents – design them to flag uncertainties and halt when needed. If an agent never refuses or never stops, it’s either perfect (unlikely) or not self-aware enough to know its limits (dangerous). Logging, in particular, is the analog of self-reflection. An agent that logs its decisions can later analyze “Did I do the right thing?” either on its own or with human help. This is similar to how pilots debrief after flights, or how we replay conversations in our head to see if we erred.

To ground this in a research example: Google’s Paperclips Experiment (a hypothetical) and real alignment research highlight that an AI pursuing a goal without constraint can go to extreme lengths (the infamous “paperclip maximizer”). The solution is never just to trust the goal; it’s to embed constraints and oversight. OpenAI’s work on AI alignment and DeepMind’s exploration of safe exploration in reinforcement learning all point to layering in inhibition-equivalents to AI. Our agentic employees should have a conscience and a supervisor – whether internal, external, or both.

In conclusion, building guardrails is not separate from building intelligence – it is part of building intelligence. As the neuroscientist Elkhonon Goldberg once suggested, inhibitory control is a huge part of why the human frontal lobes make us smarter than other animals. For our agentic AI, the guardrails are their frontal lobes. They ensure the agent’s power is channeled appropriately. A system that cannot apply the brakes or reflect on its actions isn’t advanced – it’s a runaway train. Truly intelligent agents will know when to press forward and when to hold back, and they will understand that stopping or asking for help at the right moment is a mark of competence, not failure.

Conclusion: A Shared Language for a New Workforce

The value of this Rosetta Stone is not in pushing a fanciful metaphor, but in creating shared understanding. By translating between the language of AI engineering and the language of cognitive science, we gain practical insights: we see why certain architectures work and anticipate where they might break. Engineers gain language to explain design decisions (“We need an executive-function module here to orchestrate these agents – akin to a prefrontal cortex for our system”). Leaders gain intuition for why governance – the guardrails and oversight – matters (“Even a super-smart agent needs brakes; the brain has them, so should our AI”). Operators gain clarity on where to intervene (“Ah, the agent is stuck in adapt mode – maybe I need to approve a permanent change or reset its intent”). None of this requires anyone to become a neuroscientist, just as you don’t need to be a computer scientist to benefit from the concept of a “brainstorm”. It’s about a working vocabulary that bridges disciplines.

Agentic employees are not humans, and current AI agents are certainly not sentient. But when systems persist, adapt, and learn, they inevitably begin to resemble the structures that evolution discovered first in brains. This is less magical and more mechanistic than it sounds: there are only so many good solutions to building an adaptive goal-driven system. Evolution spent millions of years exploring that space in animals and humans. We in AI are exploring it afresh in a much shorter timeframe. It’s no surprise we’re encountering analogous ideas – from assembly-like cooperation, to habit-vs-planning tradeoffs, to the need for inhibition and reflection. Understanding that convergence can prevent us from reinventing the wheel poorly. Instead, we can innovate in tandem with the lessons of biology. We can say, “If my multi-agent system is behaving oddly, perhaps there’s an organizational or cognitive principle I’m missing – do I need a better orchestrator (executive function)? Is my agent losing the plot (intent mechanism issues)? Is it thrashing (lack of habits vs adaptation balance)?” This kind of thinking leads to more robust solutions. It also demystifies AI for non-engineers: we can explain an autonomous workflow in terms a CEO or a policy-maker can grasp by analogy to human teams or brains, rather than arcane math.

Ultimately, the goal is to build them responsibly and effectively. By seeing agentic AI through the dual lens of code and cognition, we align our design with deep, proven patterns. We avoid the twin failures of naïve anthropomorphism (“the AI is basically a person”) and naïve mechanicism (“just throw rules at it, it’ll be fine”). Instead, we get a principled approach: treat an agentic system as a new type of cognitive being – not human, but also not just an if-else program – and architect it in a way that draws on what works in natural cognition while compensating for its artificial specifics.

We stand at the dawn of a new kind of workforce: part human, part AI, working together. A shared language grounded in science can help all stakeholders set the right expectations and design the right solutions. If this Rosetta Stone analogy has done its job, you now have a few more mental models (and maybe some citations to dig into!) for thinking about autonomous agents in the workplace. The hope is that this leads to agentic AI that is more capable, more trustworthy, and ultimately more beneficial as it scales up. After all, the best innovation often comes from interdisciplinary insight – in this case, the intersection of neural and silicon thinking. Let’s build the future of work with the humility to learn from the brain, and the audacity to go beyond it.

References (selected):

- Bratman, M. (1987). Intention, Plans, and Practical Reason. Harvard University Press.

- Buzsáki, G. (2010). Neural syntax: cell assemblies, synapsembles, and readers. *Neuron, 68(3), 362-385. [1]

- Ceccarelli, F. et al. (2025). Out of the single-neuron straitjacket: neurons within assemblies change selectivity and their reconfiguration underlies dynamic coding. Physiology, 603(17), 4059-4083. [2][1]

- Ebitz, R. & Hayden, B. (2021). The population doctrine in cognitive neuroscience. Neuron, 109(19), 3055-3068.

- Einstein, G. & McDaniel, M. (2005). Prospective memory: multiple retrieval processes. Current Directions in Psych. Science, 14(6), 286-290.

- Fang, R. et al. (2025). Mem⁺: Exploring agent procedural memory. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.06433. (Summarized in VentureBeat by K. Wiggers, 2025)[32][16].

- Kirkpatrick, J. et al. (2017). Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. PNAS, 114(13), 3521-3526. [25]

- Miller, E.K. & Cohen, J.D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Rev. Neuroscience, 24, 167-202. [18]

- Minsky, M. (1988). Society of Mind. Simon & Schuster (concept of mind as multi-agent system). [5]

- Park, J. et al. (2023). Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior. Proc. of ACM CHI 2023. (Stanford HAI coverage by K. Miller, Sept 2023)[21][30].

- Rao, A.S. & Georgeff, M. (1995). BDI agents: From theory to practice. Proc. of ICMAS ’95. (Belief-Desire-Intention framework for persistent goals)[20].

- Tran, K.T. et al. (2025). Multi-Agent Collaboration Mechanisms: A Survey of LLMs. arXiv:2501.06322. [3][9]

- Wang, X. et al. (2023). Voyager: An open-ended embodied agent with large language models. arXiv:2305.16291. (NVIDIA Blog by K. Yee, Oct 2023)[24].

- Additional: IBM (2023). “What is catastrophic forgetting?” IBM Think Blog.[33]; HappyNeuron Pro (n.d.) “What is inhibition in cognition?”[31]; Yao, S. et al. (2022). “ReAct: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models” (arXiv:2210.03629); Shen, S. et al. (2023). “Autogen: Enabling next-gen LLM applications via multi-agent conversation” (arXiv:2308.09254); Russell, S. (2019). Human Compatible: AI and the Problem of Control.

[1] [2] Out of the single‐neuron straitjacket: Neurons within assemblies change selectivity and their reconfiguration underlies dynamic coding - PMC

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12320208/

[3] [4] [5] [9] [19] Multi-Agent Collaboration Mechanisms: A Survey of LLMs

https://arxiv.org/html/2501.06322v1

[6] Prefrontal cortex and the bridging of temporal gaps in the perception-action cycle - PubMed

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2127512/

[7] [8] [10] Part 1: How LLMs Become Agents — The Brain, Perception, and Action of Autonomous AI | by Basant C. | Medium

https://medium.com/@caring_smitten_gerbil_914/part-1-how-llms-become-agents-the-brain-perception-and-action-of-autonomous-ai-6fa538c8f863

[11] Routine Power

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/routine-power-tim-hardman-0zy0e

[12] [17] Introducing Memp: A Framework for Procedural Memory in AI Agents | Kumaran Ponnambalam posted on the topic | LinkedIn

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/kumaran-ponnambalam-961a344_m-e-m-p-memp-exploring-agent-procedural-activity-7363938826504818689-zj2b

[13] [14] [15] [16] [32] How procedural memory can cut the cost and complexity of AI agents | VentureBeat

https://venturebeat.com/ai/how-procedural-memory-can-cut-the-cost-and-complexity-of-ai-agents

[18] Earl K. Miller & Jonathan D. Cohen, An Integrative Theory of Prefrontal Cortex Function - PhilPapers

https://philpapers.org/rec/MILAIT-8

[20] Belief–desire–intention software model - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belief%E2%80%93desire%E2%80%93intention_software_model

[21] Computational Agents Exhibit Believable Humanlike Behavior | Stanford HAI

https://hai.stanford.edu/news/computational-agents-exhibit-believable-humanlike-behavior

[22] Goal-directed and habitual control in the basal ganglia - NIH

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3124757/

[23] Understanding the balance between goal-directed and habitual ...

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352154617302371

[24] A Mine-Blowing Breakthrough: Open-Ended AI Agent Voyager Autonomously Plays ‘Minecraft’ | NVIDIA Blog

https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/ai-jim-fan/

[25] [26] [28] [29] [1612.00796] Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks

https://ar5iv.labs.arxiv.org/html/1612.00796

[27] The Rosetta Stone for Agentic Employees

https://tonywood.co/blog/the-rosetta-stone-for-agentic-employees

[30] Generative Agent Simulations of 1,000 People - Hugging Face

https://huggingface.co/blog/mikelabs/generative-agent-simulations-1000-people

[31] What is Inhibition in Cognition?

https://www.happyneuronpro.com/en/info/what-is-inhibition-in-cognition/

[33] What is Catastrophic Forgetting? | IBM

https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/catastrophic-forgetting